Reflections on a Pandemic: Insights from John M. Barry's Work

Written on

Chapter 1: Historical Context of Pandemics

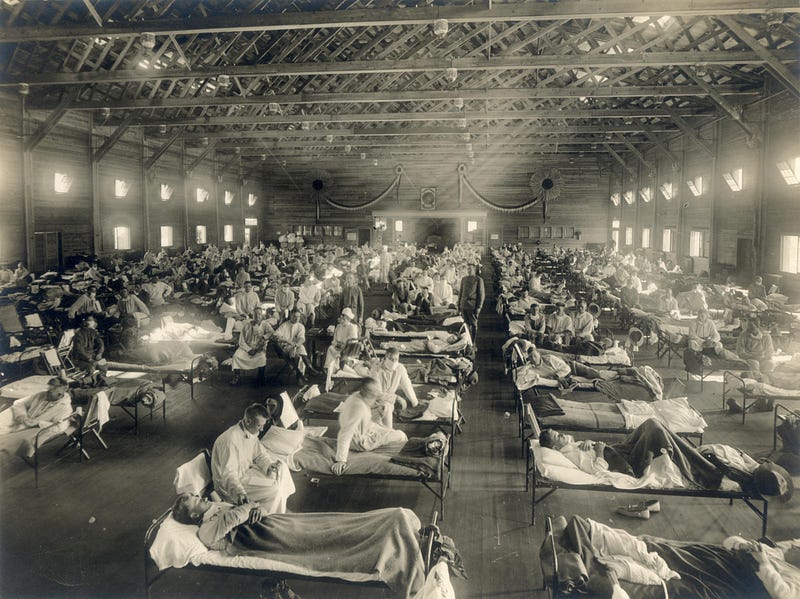

In recent times, the parallels drawn between the current pandemic and the 1918 influenza outbreak have become increasingly prominent. Commonly referred to as the “Spanish Flu” — a misnomer as it did not originate in Spain, but that nation was the first to report extensively on it — the 1918 flu pandemic remains the deadliest since the bubonic plague of the 14th century. To enhance my understanding of viruses and pandemics, I delved into John M. Barry's "The Great Influenza," first published in 2005 and regarded as the authoritative text on this topic. The book certainly met my expectations.

Barry’s profound grasp of the biological principles underlying viruses was a surprising highlight of the text. He elaborates extensively on influenza viruses, detailing how various strains differ, the factors that contribute to their deadliness, and the ways they can evolve to become even more harmful. Barry emphasizes that the morphology of viruses plays a crucial role in their interaction with human cells, stating:

In biology, particularly at the cellular and molecular levels, nearly all activity depends ultimately upon form, upon physical structure — upon what is called “stereochemistry.” The language is inscribed in an alphabet of pyramids, cones, spikes, mushrooms, blocks, hydras, umbrellas, spheres, and ribbons twisted into every conceivable Escher-like fold. Each form is defined with exquisite precision, carrying a distinct message. Essentially, everything in the body, whether native or foreign, possesses a surface form or marking that identifies it as a unique entity.

This perspective on biology is both compelling and insightful, and Barry effectively employs this line of reasoning throughout his narrative. However, he does not limit his focus to influenza; he also discusses coronaviruses, revealing a shared characteristic between them and influenza strains. He notes that:

In most organisms, genes are organized along a filament-like molecule of DNA. However, many viruses — including influenza, HIV, and the coronavirus responsible for SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) — encode their genetic information in RNA, a simpler yet less stable molecule.

Chapter 2: Comparing Past and Present

Several distinguishing features set the 1918 flu apart from our ongoing pandemic. The death rate was significantly higher, approximately 2.5%, and it uniquely impacted younger demographics, specifically individuals in their 20s and 30s. This phenomenon was attributed to the 1918 strain inducing a “cytokine storm,” where an overactive immune response posed the greatest threat to those with robust immune systems. The fatalities occurred in three distinct waves, with the second wave in the fall of 1918 being the most lethal. While it remains uncertain if COVID-19 will present in waves, this historical context is intriguing.

Additionally, the 1918 flu coincided with the turmoil of World War I, and Barry outlines how the war influenced both the virus's spread and governmental responses. Due to wartime conditions, the U.S., U.K., France, and Germany restricted media coverage of the outbreak. Although many scientists believe the 1918 influenza originated in Kansas, it garnered media attention in Spain, thus earning the moniker "Spanish Flu." The war effort took precedence, with the government urging citizens to purchase war bonds even amid the pandemic. Treasury Secretary William McAdoo proclaimed that those who refused to contribute were akin to friends of Germany. In stark contrast, in 2020, citizens received stimulus checks from the government.

Chapter 3: Societal Reactions to Pandemics

Despite the differences, many aspects of the 1918 flu still resonate with our current experience. Barry observes that “American society hardly seemed to be dissolving. In fact, it was crystallizing around a single focal point; it was more intent upon a goal than it had ever been, or might possibly ever be again.” This sentiment echoes our collective response to COVID-19, as society seems to have united around a common challenge, albeit amid political divisions.

Most areas experiencing outbreaks implemented localized shutdowns, similar to the current measures, though there were no sweeping national mandates. Barry highlights that rigorous isolation and quarantine were essential to combat the virus, yet no public health official wielded the authority to enforce such measures nationally. He recounts instances where cities were enveloped in an eerie silence, reminiscent of the fearful stillness reported in recent times:

The city was frozen with fear, frozen quite literally into stillness. Starr lived twelve miles from the hospital, and the streets were silent on his drive home. They were so silent that he began counting the cars. One night, he saw none at all. He thought, “The life of the city had almost stopped.”

Misinformation during the 1918 outbreak also parallels the current climate, with various individuals downplaying the severity of the virus. The echoes of the past resonate starkly, with statements such as “Spanish influenza — what it is and how it should be treated: . . . Always Call a Doctor/ No Occasion for Panic. . . . There is no occasion for panic.” These sentiments are hauntingly familiar in today's context.

Barry's depiction of the 1918 pandemic portrays a society grappling with fear that surged ahead of the virus itself, creating a pervasive sense of distrust. He writes:

In 1918, fear moved ahead of the virus like the bow wave before a ship. Fear drove the people, and the government and the press could not control it. Every genuine report had been diluted with lies. The more officials reassured the public, the more they stated, "There is no cause for alarm if proper precautions are taken," the more people felt adrift, with no one to trust.

This feeling of being adrift resonates with many today. However, it’s essential to identify those who are genuinely trying to help, echoing Fred Rogers’ advice to “find the helpers” during difficult times.

In conclusion, reading John M. Barry’s "The Great Influenza" proved enlightening for numerous reasons. He provided a deeper understanding of the science behind viruses like influenza and coronaviruses. Barry's narrative offers intriguing comparisons with our current pandemic, despite being published 15 years ago. The updated edition I explored also includes an afterword reflecting on recent epidemic responses, including the Hong Kong virus, avian flu, and swine flu. I anticipate that Barry is preparing to share insights on our current pandemic, perhaps leading to another edition in the near future. For now, I highly recommend diving into this insightful read. Stay safe.