Plastic Pollution: A Historical Perspective and Its Impact

Written on

In September 1966, biologists Karl W. Kenyon and Eugene Kridler journeyed to Southeast Island in Hawaii. Tasked by the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, they were on a mission to locate Laysan albatrosses within the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge. As they navigated the island's shores, they were met with picturesque landscapes where cloud-colored sands met the ocean waves. However, their search revealed a troubling sight: the lifeless bodies of numerous young albatrosses, all perished before they could take flight. Along the coastline, they noted that many more had been reduced to fragments by the relentless wave action.

Reports of seabirds ingesting “indigestible materials” had surfaced as early as the 1950s, raising concerns about the estimated 450 to 500 deceased birds on the island. Yet, it wasn't until Kenyon and Kridler's investigation that a comprehensive examination of the specific types of indigestible materials these birds consumed took place. Their analysis of the stomach contents of dead Laysan albatross chicks marked one of the earliest scientific acknowledgments of oceanic plastic pollution.

Kenyon and Kridler collected samples from 100 albatrosses. Upon investigating the birds' digestive systems, they uncovered remnants of bone, charcoal, wood, pumice, fishing line, squid beaks, and plastic debris. Their focus on plastic yielded findings of bottle caps, plastic tubing, toys, and polystyrene bags. Alarmingly, 74% of the sampled chicks had ingested plastic before their untimely deaths.

These young albatrosses depend on their parents for sustenance until they can fly. Known for their monogamous partnerships, Laysan albatrosses share parental duties. The adults alternate between incubating eggs and foraging in the ocean. Unfortunately, plastic floating in the water can resemble a meal to these birds. Mistaking it for food, they bring back harmful debris to their nests, potentially leading to blockages in their chicks' digestive systems, which can cause fatal consequences.

Kenyon and Kridler concluded that the deaths they observed were due to plastic and other indigestible items being consumed by the chicks after being regurgitated by their parents. Their findings illustrated a larger issue; by 1966, plastic pollution had already permeated remote islands in the Pacific. They noted that a neighboring atoll's lagoon was strewn with small plastic objects and pumice, concluding that this waste must have originated from dead birds rather than ocean currents.

The image of a beach littered with plastic from decomposing seabirds is grim, yet it reflects a broader ongoing crisis. Today, nearly 70% of the Laysan albatross population nests on Midway Atoll, where young birds consume approximately five tons of plastic each year. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that about 25% of albatross chicks die before fledging, with Greenpeace suggesting that the figure could be as high as 40%. In contrast, Kenyon and Kridler documented a mortality rate of only 4 to 10% in 1966, a time when plastic pollution was still emerging.

Since Kenyon and Kridler's research, humanity has produced over 8 billion metric tons of plastic, nearly quadrupling the total carbon-based biomass of all animal life on Earth. By 2050, plastic waste is expected to reach 34 billion metric tons, with threats to Laysan albatrosses and other seabirds rising in tandem with plastic pollution. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences indicates that as plastic in the ocean increases, so will ingestion rates among seabirds.

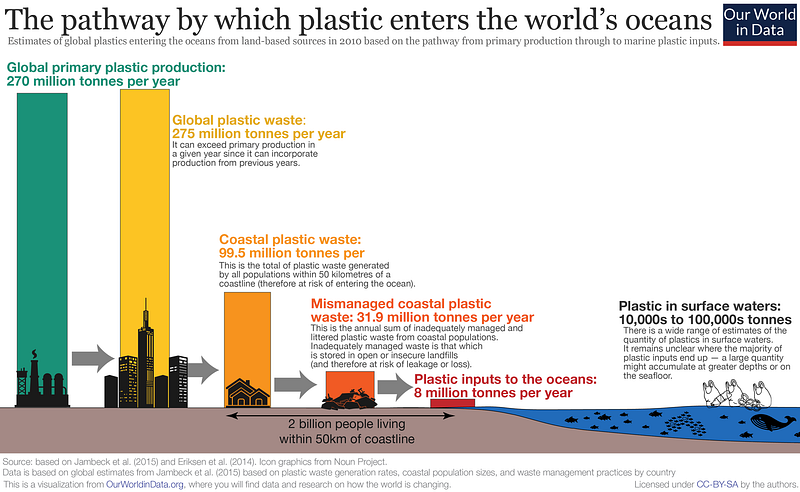

Each year, around 380 million metric tons of plastic are manufactured, and between 4.8 to 12.7 million metric tons of this newly created plastic end up polluting the oceans. Currently, an estimated 150 million metric tons of plastic float in Earth's oceans, and projections indicate this number could triple by 2040. Much of this plastic is carried by ocean currents toward the Laysan albatross's nesting areas, where it is mistakenly fed to unsuspecting chicks.

However, the Laysan albatross is not alone in facing the dire consequences of plastic pollution. Research indicates that by 2050, 99% of ocean seabird species will likely ingest plastic, with over 95% of individual birds from these species affected.

The decline of ocean seabirds is alarming; between 1950 and 2010, approximately 70% of the world's seabird population vanished, with more than a million seabirds dying each year due to plastic pollution. The Laysan albatross specifically is projected to see a 30% population decline by the century's end.

Plastic pollution also severely impacts marine mammals, claiming the lives of over 100,000 each year, according to UNESCO. A 2016 United Nations Environmental Programme report indicated that more than 800 marine species were threatened by oceanic plastic pollution, a number that rose to 1,450 by 2018, affecting creatures of all sizes and habitats.

Consider a simple plastic bottle cap adrift at sea, a common item that Laysan albatrosses might mistake for food. As time passes, this plastic degrades into smaller particles known as microplastics, which resemble grains of sand. Sadly, microplastics also mimic food, entering the diets of marine life. These tiny particles can disrupt the food web, as they mix with marine snow—organic matter that nourishes deep-sea creatures.

Research has shown that amphipods, tiny shrimp-like crustaceans in the Mariana Trench, now consume microplastics instead of their natural diet. This shift leads to similar health issues as those faced by Laysan albatrosses, including intestinal blockages and potential mortality. Trillions of microplastic particles are present in our oceans, and billions of larger plastic pieces float or sink, affecting species from the smallest amphipods to the largest blue whales.

Humans are not immune to the repercussions of plastic pollution. Through our air, water, and food, the average American ingests an estimated 70,000 to 121,000 microplastic particles annually. Once inside our bodies, these particles can cause numerous health issues, including oxidative stress and DNA damage. Compounds like bisphenol A (BPA), a common component in plastic, pose serious health risks, having been found in 93% of Americans tested by the CDC. BPA is linked to various health problems, including growth and behavioral issues, and may have more significant effects than previously thought.

While "plastic pollution" may evoke images of bags and bottles in remote oceans, the reality is far more pervasive and insidious. Its impacts reach well beyond distant shores, touching lives across the globe.